Days of My Youth: Remembering the Past to Appreciate the Present

I was born and raised in an impoverished hamlet during a difficult time for our country. My parents worked from early in the morning to late evening, 365 days a year, to bring up five children, boys and girls. However, we still did not have enough food or clothing. We ate anything we could find to comfort the gnawing in our stomachs. I remember we ate the trunks of banana trees, and sorghum, a staple for cows. The problem is that the human body does not generate the necessary enzyme to digest it, so eating foods like these only pacified our stomachs temporarily, giving them the feeling of being full. They went in and came out of our system looking almost the same.

My mind went back to a photo I had once seen of a North Korean man uprooting grass to eat. Places where people suffered so much were hells on earth, created by evil doctrines. Foolish ideologies caused the degeneration of human values in a society where materialistic inclinations controlled all morals and social relations. Ironically, those who are starving have been taught to call those who brought them this earthly hell their “founding fathers” or “saviors.”

My family and I lived in a crumbling house made of bamboo and cow dung, with a simple dirt floor. All five siblings slept on a bamboo bed, covered with a blanket made of old fabric bags sewn together. In those days, people even fought over fallen leaves, since we used leaves as a main fuel for cooking. Wood was a luxury. On weekends, my dad would often walk to a forest twenty kilometers away from home to fetch wood and carry it home on his shoulders. He would start out at two in the morning and come home late in the evening, just to gather fuel for about two weeks. I still remember vividly one of those trips, when he came home without wood, but instead just a bloody wound on his knee, where he had bandaged himself with a piece of his shirt. He had accidently hurt himself with the axe. I was seven at the time.

My family and I lived in a crumbling house made of bamboo and cow dung, with a simple dirt floor. All five siblings slept on a bamboo bed, covered with a blanket made of old fabric bags sewn together. In those days, people even fought over fallen leaves, since we used leaves as a main fuel for cooking. Wood was a luxury. On weekends, my dad would often walk to a forest twenty kilometers away from home to fetch wood and carry it home on his shoulders. He would start out at two in the morning and come home late in the evening, just to gather fuel for about two weeks. I still remember vividly one of those trips, when he came home without wood, but instead just a bloody wound on his knee, where he had bandaged himself with a piece of his shirt. He had accidently hurt himself with the axe. I was seven at the time.

When I was fourteen, a couple of boys in my village and I rented a two-wheel cart and went to a pine wood to collect needles, with a homemade raker. There were not enough fallen needles, so sometimes we broke off fresh branches from the trees. A huge, heavy cart stuffed with pine needles being pushed and pulled by scrawny children up and down many slopes of a distance more than fifteen kilometers—an image that would win a Pulitzer Prize!

Water supply was a big issue, too. Fifty neighboring households shared one water outlet in the middle of the hamlet. To avoid waiting in a long line, we had to get there after midnight. The water was not sterilized, and we did not have enough wood to boil it before drinking, so it commonly transmitted contagious diseases, such as cholera and dysentery. Outbreaks of cholera occurred several times and killed many people, especially children.

The only means of transportation for our family of seven was an old bicycle. A bike was so valuable that in order to trade one, the signatures of government representatives and witnesses were required. A cousin of mine rode a bike the distance of five hundred kilometers to an alumni reunion in Qui Nhon. The only food he had during his weeklong trip was bananas. My older sister commuted five kilometers every day to school on foot. She wished to have a bike, but my family could not afford it. She had to quit school to help my parents take care of our siblings.

I started working for money at age nine. I did everything I could, from making fishing nets, to catching shrimp and fish, to raising pigs and planting and harvesting on farms. Many people still remember me as the fastest net maker, a job requiring the dexterity of a woman. The summer I was in eighth grade, my sister, a few other people and I got up at three in the morning to walk to a village north of my hometown. We arrived at sunrise and began a day of work helping farmers. We picked peanuts from their plants and got paid for the number of baskets we filled. The kind farmers often served us delicious- smelling roasted peanuts at lunch.

Behind my house were three ponds situated next to each other, in which government staff raised fish. The inhabitants of the hamlet often stole the fish, so guards usually kept watch in the shack located on the dyke of the middle pond. The fish were fed grass and toilet waste. Every day a tanker truck carried human feces to the ponds and pumped this “nutrient” into the water via a rubber hose at the corner of a pond. The residents of our neighborhood were disgusted by the foul smell, but we lived with it, just as we tolerated other filthy conditions at the time. In summer, children often stole fish from the ponds with fishing rods. The fish were so hungry that they would eat anything we used for bait. We caught quite a few fish which provided a much-needed source of protein as a supplement to our meals, which were otherwise severely nutrition-deficient.

Behind my house were three ponds situated next to each other, in which government staff raised fish. The inhabitants of the hamlet often stole the fish, so guards usually kept watch in the shack located on the dyke of the middle pond. The fish were fed grass and toilet waste. Every day a tanker truck carried human feces to the ponds and pumped this “nutrient” into the water via a rubber hose at the corner of a pond. The residents of our neighborhood were disgusted by the foul smell, but we lived with it, just as we tolerated other filthy conditions at the time. In summer, children often stole fish from the ponds with fishing rods. The fish were so hungry that they would eat anything we used for bait. We caught quite a few fish which provided a much-needed source of protein as a supplement to our meals, which were otherwise severely nutrition-deficient.

One day in the summer of my eighth grade, a friend and I went fishing. The water was so shallow that we had to wade into it to fish. We did not want our clothes to get wet, so we took them all off, and stepped into the water. It was a terrible decision. Two guards snatched us from the water. They did not let us put our clothes back on, and walked us stark naked to their central station one kilometer away. We tried our best to use our hands to cover what we needed to hide on our bodies. A real “Naked and Afraid”, not just a reality TV show. When we walked by the house of a girl from my class, my heart was racing. Fortunately, she did not run outside to see me. (I dared not ask her later if she did watch me through a hole in the wall.) At the station we were spanked ten times on the buttocks with a bamboo rod, and retained there several hours, then released much later in the afternoon. Embarrassed by our exposed bodies, we tried to hide ourselves using the many ponds that lined our pathway home. My parents did not find out this incident until twenty years later. They asked me why I had not told them about it.

When I was at the guards’ station, I thought of taking revenge one day, when I became big and strong enough. About ten years later, I ran into one of the guards at the wine party of a mutual friend. He did not remember me. I had a lot of wine to drink that night, but I felt at peace inside, with no anger or hatred against the man. He belonged in my past. “Let bygones be bygones…”

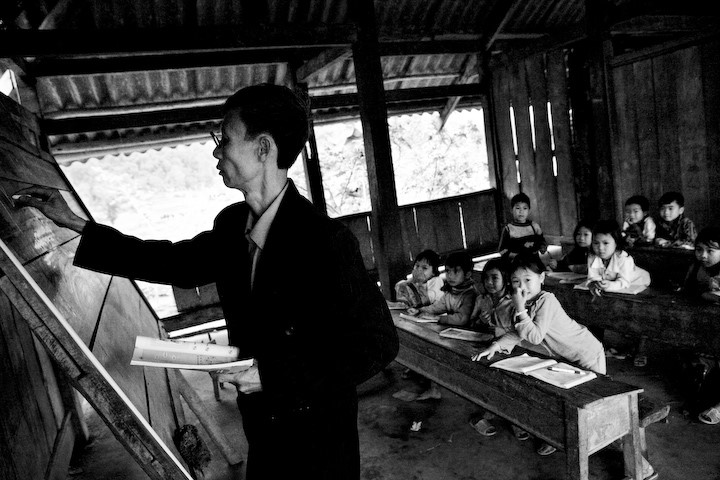

In middle school, I was impressed with a teacher named Nho, the best I have ever had. He could teach any subject, from math to physical education. Sometimes he brought to class a shabby suitcase containing dozens of seemingly random objects, such as hats, scissors and gloves. First, he would open the suitcase for about thirty seconds so we could peek inside, then he would close it, and ask us to name as many items we had seen as we could. His way of teaching was so interesting that I did not want the classes to end.

Many times, when Nho was standing in front of the blackboard, some of my classmates grumbled, “Mother fucker! Don’t listen to that burglar!” They lived with him in a squalid neighborhood. They told all the students that Nho stole several things from his neighbors. He allegedly caught a chicken from one neighbor at nighttime, and picked a jackfruit from another when it was still unripe, and put it above the kitchen to help it ripen faster. Many times he and his children were caught red-handed. I was not sure whether what my classmates said was true or false, and I really did not care. For me, that did not matter. I felt pity for him, but that did not lower my respect for him, my best teacher. Who knows, he might have been guilty of all those allegations, but he must have had good reasons for doing so. He had many children, and if they were starving, he possibly did steal to survive, just like in Jean Valjean’s case. Nho’s children are now successful adults, and I believe that they will never have to repeat their disgraceful past.

Many times, when Nho was standing in front of the blackboard, some of my classmates grumbled, “Mother fucker! Don’t listen to that burglar!” They lived with him in a squalid neighborhood. They told all the students that Nho stole several things from his neighbors. He allegedly caught a chicken from one neighbor at nighttime, and picked a jackfruit from another when it was still unripe, and put it above the kitchen to help it ripen faster. Many times he and his children were caught red-handed. I was not sure whether what my classmates said was true or false, and I really did not care. For me, that did not matter. I felt pity for him, but that did not lower my respect for him, my best teacher. Who knows, he might have been guilty of all those allegations, but he must have had good reasons for doing so. He had many children, and if they were starving, he possibly did steal to survive, just like in Jean Valjean’s case. Nho’s children are now successful adults, and I believe that they will never have to repeat their disgraceful past.

During my high school years, my teachers often asked me why my hair was so yellow. They did not know that it was dyed with ferric sulfate in the pond water where my sister and I went diving every night to catch shrimp. My sister took the shrimp to the market to sell every morning so she could go to school in the afternoon.

As I have said before, I worked on a farm and raised pigs. Can you guess how many of them I raised at a time? The number could not be zero, so it was one. We used the waste from the pig to fertilize the vegetables, some of which later would go back into the pig’s stomach—a full cycle.

I want to say a little more about the piece of land we used to plant our crops. It used to be a battlefield during the Vietnam War. After North Vietnam occupied the South, the land was subdivided and distributed to many families for farming. No technical training or equipment was provided for the risky work in an area riddled with hidden dangers left behind by the war. As a result, many people were wounded or killed in mine field explosions. We were afraid of mines, but we still worked on that land, because hunger was even more powerful than the fear of being killed.

My dad was a government construction worker so he received coupons to get food at government stores. His monthly rations consisted of fourteen kilograms (about thirty pounds) of rice, and 0.7 kilograms (one and a half pounds) of pork. To get them, my dad had to be in line from midnight to about six in the morning. After that, I took his place in line at the stores so he could go to work. It usually took us about twelve hours to get one and a half pounds of pork that was no longer fresh, but you could not imagine how wonderful it tasted to us. Sometimes, we waited until noon just to be informed that the rice had run out, so we had to come back and be in line again another day. That kind of thing was not a big deal in “the paradise” of socialism.

My dad was a government construction worker so he received coupons to get food at government stores. His monthly rations consisted of fourteen kilograms (about thirty pounds) of rice, and 0.7 kilograms (one and a half pounds) of pork. To get them, my dad had to be in line from midnight to about six in the morning. After that, I took his place in line at the stores so he could go to work. It usually took us about twelve hours to get one and a half pounds of pork that was no longer fresh, but you could not imagine how wonderful it tasted to us. Sometimes, we waited until noon just to be informed that the rice had run out, so we had to come back and be in line again another day. That kind of thing was not a big deal in “the paradise” of socialism.

For many families, including ours, the food we obtained one day was just enough for the next, but we did not often achieve this vital goal. Therefore, many times we had to carry a bamboo basket to the homes of our close relatives to borrow some rice. We used an empty condensed milk can to measure it. When I tell my kids now about those days, they’re hard for them to imagine.

Next to our house was a single mother with four kids. They ate twice a day. After a meager breakfast, and before the mother went to work, she hanged the rice portion for dinner high up under the roof of the house, out of the reach of her children. Many times, I heard her yell at them for poking the suspended bag of rice with a long stick and eating every grain of the uncooked rice fallen to the ground.

I only had two sets of clothes for the three years I was in high school. One of the two pairs of pants I owned was a hand-me-down from my sister. When the pants were worn out on the backside, I took them to a tailor, who reinforced the damaged part with a piece of fabric, and mended it with spiral seams. One male friend of mine in high school told me I drew parabolas and hyperbolas on my pants. (He was often in jeans. I could only dream of them.) He said so probably because he thought I was good in math, and he did not mean anything bad by it. At that time, though, I thought he was mocking me. At a reunion twenty years later, I told him about what I had thought of his remark. He got angry with me and left the party early. Twenty years earlier, I misunderstood him, and now, he did the same thing to me. So we are even.

The story of my poor pants did not stop there. When the mended part wore out again, my sister’s friend altered the pants and gave them a new shape, by turning them upside down, making the waistband into the lower hems, and the hems into a waistband! Does anyone today have a real attachment to their clothes the way I did with those pants of mine? I still remember them now, after all those years. Our clothes had their own lives, and such glorious ones, indeed. We truly appreciated them, almost as if each of them had its own soul and tried its hardest, down to its very last thread, to fulfill its duty to serve us.

My mother has always regretted not letting me attend the advanced class for the entire province because it was too far away from our home. When I grew up, sometimes I complained to her about that, but then I realized she had to make that decision. We really had no choice. My classroom had shabby windows that could not protect teachers and students from rain and wind. Other than basic textbooks, the only book I got to read hundreds of times in elementary school was “The Life of Animals.” My cousin had received it as an award for his performance at school. It was a story in black and white, about how animals lived in nature. The sole entertainment for hundreds of children in my hamlet was watching TV in the evening. A so-called “richest family” had one TV set that the host kindly let the poor scruffy kids watch. I do not remember why I was one of the few kids who rarely went there to watch the interesting programs.

We did not have any concept of vacation. These days, when going on vacation with my own family, I often think of my parents. They never had a minute to relax. Holidays were sad days for us. I never welcomed New Year’s days, a real nightmare. On those days, while many people were going to town for playing or sightseeing, my father would use his rickety bicycle to carry passengers for money. My mother would sit in a corner of the house, staring at an infinite point in space. I believe the impact of extreme poverty on mental health may be more severe than on physical health. I have witnessed so many soulless bodies in my life. Such misery!

It is very common to praise children from poor families when they overcome adversity to prevail in their education. For me, though, I admire individuals from wealthy families who have almost everything, without the high level of pressure and motivation the poor have, and yet, they still work hard to earn their independence and success. This part reminds me of the cold winter nights when my sister and I went to catch fish in a pond behind our house. I often looked up at the stars in the dark sky and wished we would someday break the cycle of poverty.

Thanh Nguyen YKH-29